A new era for sustainable development

In 2015 world leaders stand poised to chart a new course for sustainable development. The Sustainable Development Goals they adopt, the climate change deal they strike, and the subsequent pacts that follow, will all serve to frame international development cooperation for the next 15 years.

If they are to end poverty, raze inequalities, and safeguard the world's ecological health, they must speak to the needs and priorities of the world's most vulnerable citizens and communities, and reflect the diversity of credible research, including that from the Least Developed Countries (LDCs).

IIED has long worked to amplify the voices of marginalised groups in decision making, and over the past 12 months we have focused much effort on the debate and diplomacy leading up to the year's landmark summits. From assessing the fairness of who pays for change, to supporting LDC negotiators, we have been doing what we do best: linking local priorities to global challenges.

This online annual report offers a snapshot of our work over the past year. Navigate to read stories about some of our programmes and projects, and learn how IIED is making a difference.

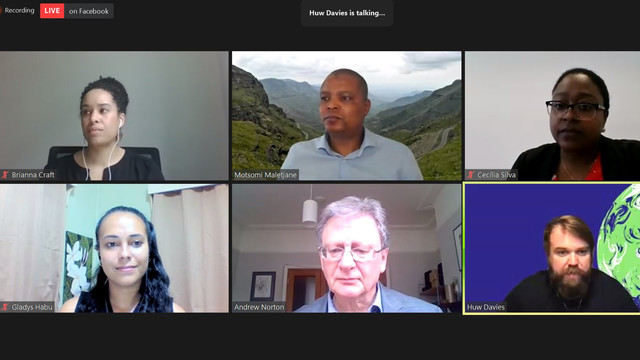

More videos from Andrew Norton:

A framework for a fairer future

After three years of debate and negotiation, 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have been developed to provide a blueprint for a fairer, greener world that balances the economic, social and environmental dimensions of prosperity and human well-being.

These were due to be adopted in September 2015 to drive the global development agenda until 2030. But can they really fulfil global ambitions to tackle poverty, reduce inequality, combat climate change and protect ecosystems?

This year, IIED commissioned an animation to capture the universal ambition set out in the SDGs by presenting the lives and hopes of five characters around the world. It calls on citizens everywhere to speak out and hold global leaders to account: to recognise our responsibilities and demand the future we want.

Bringing the SDGs to life: real change for real people

Highlights from our work on individual goals

Uganda

Looking at the world from each other's point of view, using integrated multidisciplinary approaches to address some of the world's most pressing problems – poverty, disease, population growth, environmental degradation and climate change – will make it easier to shape a fairer future.

Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka, founder and CEO, Conservation Through Public Health

Trinidad

Nicole Leotaud, executive director, Caribbean Natural Resources InstituteA fairer future means equity - with community enterprises supported in the economy, good governance with civil society having a real voice in national development – and justice, where Caribbean islands are supported to adapt to climate change impacts caused by others.

Bangladesh

Farah Kabir, country director, ActionAid; and member of the Least Developed Countries Independent Expert GroupA fair future is possible if global leadership seriously commits to achieving climate justice that is gender sensitive and poor-centric. Global leadership must manifest their commitment to gender and climate justice that will transform the world moving it towards a new world.

Kenya

Chemuku Wekesa, research scientist, Kenya Forestry Research InstituteIf we are to achieve a fairer future we must 'power-up' smallholders to produce enough quality food for their families and communities. That means investments that promote sustainable agriculture, help farmers adapt to climate change, and, most importantly, keep the needs and priorities of smallholders central.

Chile

A fairer future would be one in which our opportunities in life were not determined by the place and situation in which we were born and raised.

Dr Julio A Berdegué, RIMISP Centro Latinoamericano para el Desarrollo Rural

India

Reetu Sogani, Lok Chetna ManchA fair future would be one in which indigenous knowledge, resources and sustainable living traditions are given the most respect, and are not considered mere inputs to sectors such as agriculture, health or natural resource management systems.

Kenya

Margaret Waithera Mwaura, student, University of NairobiWhen it comes to development, everyone has a role to play, no matter how small. A society that promotes equal opportunity – especially through education for all regardless of gender, creed and race – is aiming for a fairer future.

Colombia

Lina Villa, executive director, Alliance for Responsible MiningA fairer world is one where individuals and organisations act, not out of the fear of being accused, marginalised, penalised or raided, but out of the realisation that the future of all peoples, economies and ecosystems are fundamentally intertwined.

Switzerland

Youba Sokona, special advisor on sustainable development, the South Centre; and member of the Least Developed Countries Independent Expert GroupIn the post-2015 era we have a unique opportunity to integrate human development and environmental sustainability. In doing so, we must consider each country in the context of its national development objectives, addressing both short- and long-term imperatives.

Malawi

Ibidun Adelekan, Urban ARK projectA fairer future would be the opportunity for all peoples to live in a healthy, risk-free and food-secure world, in which there is equity in access to nature's resources and quality social services.

Indonesia

Ronnie S Natawidjaja, director, Center for Agrifood Policy and Agribusiness Studies, Padjadjaran UniversityIt is projected that, by 2020, 80 per cent of the Indonesian population will be in urban areas. However, the urban space is not designed to accommodate the poor and informal sectors of society. These people are often marginalised, harassed, and removed from the public areas. A fairer future would be one in which urban growth is more pro-poor and supportive of stronger rural-urban market links in the face of globalised markets - particularly in food systems.

48,000 people will be displaced by the planned Fomi dam in Guinea

150 large-scale dams have already been built in West Africa; 90 of these support irrigation

Turning tides: making West Africa dams fairer for all

In West Africa, governments often view large dams as a panacea for development. Dams offer the potential to generate power, irrigate crops and provide jobs and money - but for whom?

If dams are a cure-all, they must work not only at the national level, but also to serve the rural communities that live on the land earmarked for construction or flooding.

Through the Global Water Initiative in West Africa, IIED and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) are working to protect local rights and livelihoods. These photos, taken for GWI West Africa in villages around the Sélingué dam in Mali, show that when it comes to supporting local smallholder farmers, one size won’t fit all.

Dr Aboubacar Sidiki Condé, Director General for Fomi dam project, GuineaIf it weren't for the real involvement of GWI in this process, and consultation with the people through these [feasibility] studies, we could not do them. In fact, this is a first here in Guinea.

Our land, our choice: the case for locally-led adaptation funds

An innovative pilot project in Kenya is putting local people in control when it comes to financing adaptation to climate change – and results have been impressive.

The project has set up 'County Adaptation Funds' in five Kenyan counties that are subject to severe drought. It puts money directly into the hands of pastoral and agro-pastoral communities, empowering them to draw on their knowledge of the land and climate to adapt to climate change.

IIED is a member of the Adaptation Consortium, which is piloting the project. This year the adaptation fund in Isiolo County completed its second round of investment, which included £500,000 from the UK government.

Working with traditional local institutions, or 'dedhas', Isiolo's county government, supported by the Adaptation Consortium, has evaluated the impact of the first round, and the findings showed some clear successes...

The assessment found that communities are better prepared for late or limited rains. This has been achieved through stronger local governance mechanisms that work to protect dry season grazing lands. The results are reduced livestock losses and maintained productivity.

The improved local governance and management mechanisms have helped communities conserve more water. They are building and repairing water infrastructure, such as pans, wells and boreholes, and the water is being kept clean and disease free. The result is that clean water is available for longer through the dry season than ever before.

The Country Adaptation Funds are giving power to local people. In Isiolo, 70 per cent of funds must be invested in activities prioritised by local communities, through ward planning committees. These committees are responsible for hiring and managing all suppliers and service providers, and many of the wards in Isiolo are working on strengthening their governance mechanisms.

What's next?

Isiolo's approach is proving to be both tactical and sustainable – aiding best use of existing resources and building collective knowledge to face future extremes. The results are cause for confidence in what can be achieved with future investment.

In the next year the Isiolo County Adaptation Fund is likely to become a public fund. This means it will be able to draw on national and county budgets and be less reliant on foreign aid. Importantly, this will allow Kenya's National Drought Management Authority to access the UN’s Green Climate Fund for adaptation financing.

IIED is proud to be part of the consortium that has worked on this pioneering project. Its decentralised funding model reflects IIED's belief in self-determination: a fair share of climate funding, in local hands, can be a powerful model for poor communities around the world.

Hussein Konsole, ward committee chairman and younger dedha member, KenyaDedha is a local institution that has been there [to] manage all water points and solve conflict. When you empower dedha you empower the whole community – you make them resilient against all shocks of drought.

New prospects for informal gold miners

Artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) is characterised by informality, environmental risk, operational dangers and social and political marginalisation. Its sheer scale offers huge potential for social transformation: ASM forms the livelihood for an estimated 20-30 million people, including many of the world’s poorest citizens.

IIED has begun an ambitious programme of work designed to encourage a move to more responsible and inclusive mining. Working with partners, we are mapping the ‘ASM landscape’: the people involved and their relationships and realities. Our work is rooted in reality: we travelled to Tanzania's Geita gold mining district to discover the human stories of diggers, drivers, geologists, mining officers and village elders. Their images provide a constant reminder of their perspectives.

ASM has many stakeholders, including artisanal miners, small and large mining companies, governments, civil society and donors. Bringing these interest groups together is no easy task. In April, we organised an international meeting for more than 40 ASM stakeholders. By the end of this ‘visioning’ workshop, we had agreed that in a sector where most miners operate informally, developing and implementing good formalisation policies that enshrine land, mineral and human rights will be critical.

We are now planning a series of in-country dialogues on ASM, where local stakeholders can identify their own context-specific challenges and opportunities. The first event is scheduled for Ghana in November, 2015. We will work with a local partner to ensure the dialogue is grounded in the local context, with parity of voice across all stakeholders, including artisanal and small-scale miners.

We are also working with the Alliance for Responsible Mining and others to develop a common framework and toolkit for achieving a more inclusive and sustainable sector.

James McQuilken, University of Surrey Business School, UKWith key stakeholders all in the same room for the first time, this was a great opportunity to focus on potential solutions to some of the issues… Providing a unique global forum, [ASM] stakeholders from across the Americas, sub-Saharan Africa and Asia were able to share their knowledge, experience and perspectives collectively for the first time.

Ghana's gold in numbers

1.5 million

ounces of Ghana's gold - 35.4% - was produced by formal small-scale mining in 2014

1 million

people are employed in Ghana's ASM sector, with several millions more involved in related industries

10%

of artisanal and small-scale miners in Ghana are women

80%

of artisanal and small-scale miners in Ghana operate without a legal licence

Two thirds of the global population will live in urban areas by 2050. By far the largest growth will be seen in Africa and Asia

Mapping the fresh challenges of urban food security

The 2.5 billion increase in the global urban population predicted for 2050 raises pressing questions about food security. Most population growth is expected in low-income and informal settlements in Africa and Asia, and this is where we must look for answers.

A key problem with food security is not that there is not enough food to eat, but that many people do not have enough food to eat.

Many people in informal settlements manage an unreliable food supply by simply reducing the quality and quantity of their meals. This is a recipe for illness and inequality.

In this landscape, street vendors are becoming more central to the eating habits of low-income households. Street vendors are often seen by authorities as sources of unsafe food, polluters and obstacles to development. But the truth is that they support food security by selling affordable cooked foods and creating employment for many poor urban dwellers.

IIED and partners are working with Kenyan federation of slum dwellers Muungano wa Wanavijiji to reach out to street vendors and their customers, as well as people keeping livestock in Nairobi’s informal settlements.

A balloon mapping exercise, using aerial pictures taken about 100 metres above ground, gave residents accurate, up-to-date maps of their settlements. These maps are allowing Nairobi’s disenfranchised inhabitants to identify and implement solutions to the challenges prioritised by their communities, particularly in relation to food safety.

This work is also feeding into a wider, more accurate narrative on urban food security.

Participant, IIED focus group discussion, Mathare, Nairobi, KenyaThe way we eat in informal settlements has changed over time. We prefer ready-cooked food because we lack adequate cooking spaces in our shanties and more so we are prone to fire outbreaks.

We reduced our emissions by 2.5%

We spent £18.1m in 2014-15

109 people; 32 different languages

770,341 of our research publications were downloaded