Q&A: How to negotiate safe access to gang-ruled neighbourhoods in areas of urban crises

In the latest issue of Environment & Urbanization, Moritz Schuberth examines the added difficulties humanitarian actors face when dealing with crises in urban neighbourhoods ruled by gangs. Schuberth studied the neighbourhoods of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake to find out how agencies can deliver the most effective response.

What's your journal article about?

What's your journal article about?

My article investigates how humanitarian and development actors negotiated safe access to gang-ruled neighbourhoods in Haiti's capital Port-au-Prince, following the 2010 earthquake. My focus was on finding out how international agencies can deliver humanitarian relief and development aid to those who need it most – but without paying off predatory armed gangs, which would inadvertently strengthen them.

First, some context: what's the difference between gangs in urban and rural contexts?

Since Thrasher's influential work on the gangs of Chicago in the 1920s, gangs have been studied as an essentially urban phenomenon, indeed as the very outcome of the urban ecosystem. Rural areas in many countries – including Haiti – have seen the rapid growth of armed groups, such as rebel groups or paramilitaries. But these are not typically seen as gangs.

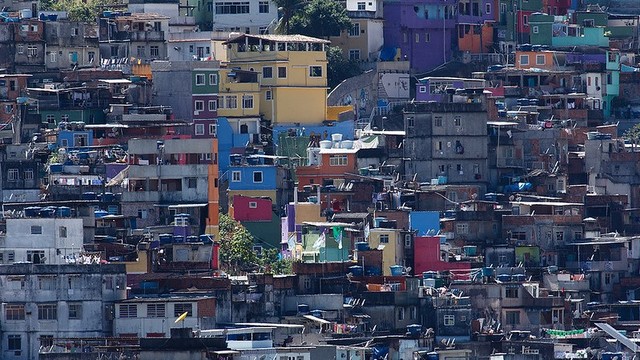

An important aspect of gangs in capital cities such as Port-au-Prince is their location – positioned at the economic and political heart of the country. On one hand, this means that economic and political elites can instrumentalise gang members for their own interests, as demonstrated most notably in Haiti during Jean-Bertrand Aristide's second presidency from 2001 to 2004. On the other, gangs can cause a lot of disruption, such as by blocking a country's main artery roads. Using such tactics, gangs can effectively shut down megacities such as Rio de Janeiro and paralyse the economy.

So in practice, what does gang violence mean for humanitarian agencies operating in an urban crisis response?

Gang-related violence is a major challenge for humanitarian agencies operating in urban settings. I found some international agencies had very little knowledge of how to work in areas controlled by gangs. They had no plan on how to engage with gangs when they entered their neighbourhoods. They therefore had to choose between simply paying off gang leaders who threatened their staff at gunpoint, paying gangs indirectly by hiring their leaders as community mobilisation officers, or not working in gang-controlled areas at all.

The upshot is those living in these neighbourhoods are forced to cope with gangs that have been strengthened financially by international agencies, or missing out on vital humanitarian assistance.

The research showed a few actors following two less harmful practices. These require sound understanding of how things work on the ground, but might be options for agencies planning to work in comparable contexts: either entering neighbourhoods under the control of gangs with the protection of what might be called the "genuine" civil society – as opposed to gangs posing as civil society – or integrating gang leaders in community platforms in which they are sidelined by non-criminal leaders who represent the community.

These findings reveal the growing challenge for international agencies as they try to navigate armed gangs while seeking to access areas affected by conflict and disasters.

Why is it important to work with urban armed gangs at the local scale?

It's important to have some peacebuilding actors working at the community level with all actors, including gangs: gang culture in urban areas is real and rife – it cannot be ignored.

My research found that when agencies integrate working with gangs into their programmes, they are much better equipped to deal with them compared to agencies that engage with gang leaders only to gain safe access for their staff. For example, by organising workshops on conflict resolution with gang members, agencies can learn how to navigate the challenge of gang violence and so can get humanitarian support to the neighbourhood more effectively.

NGOs such as Viva Rio see constructive engagement with gangs as an end rather than a means. They can act as a gatekeeper for other international agencies simply wanting to implement emergency relief or development projects in gang-ruled areas. This can help build the resilience of urban communities under the control of armed groups by getting assistance to those who need it the most while reducing harmful practices such as paying off gang leaders.

Could you expand a little more on the work of Viva Rio?

Viva Rio came to Haiti after gaining extensive experience working in gang-controlled favelas in Brazil. In Port-au-Prince since 2007, they have established themselves as an important actor in the Bel Air neighbourhood, implementing peace accords locally known as Tambou Lapè. These accords reward the absence of violence with lottery draws that seek to incentivise gang members to observe self-imposed rules, such as not stealing from within their own community.

In recent years, the peace accords have evolved from establishing a truce between rival gangs into building a community structure made up of various local actors. This structure helped Viva Rio and other international agencies implement emergency relief and development projects in the neighbourhood.

What recommendations did you draw from your work? Could they be applied to other urban contexts with armed gangs?

My research underlines how important it is for humanitarian or development agencies planning to work in gang-controlled areas to complete a do-no-harm assessment before implementing their activities. From the very beginning, paying off criminal groups to gain access to their turf must be ruled out.

Instead, agencies could try to enter such neighbourhoods under the protection of influential civil society groups or local leaders. While this approach is more likely to be respected by gang leaders, agencies should make sure that the civil society groups with whom they enter are not gangs in disguise and do not have too close ties to the gangs.

During the planning phase, a mapping exercise of the different actors in the intervention areas and the relationships between those actors can help build an understanding of how things work on the ground. Local or international NGOs that have been working closely with the community and/or have peacebuilding projects aimed specifically at armed groups can play a crucial role here.

This highlights the importance of working collaboratively with multiple actors – Haiti has so far been a textbook example of where lack of cooperation and coordination among different international and local actors has duplicated efforts.

While I believe the findings from the Haitian case can provide important lessons for comparable urban contexts, I think it is equally important to approach criminal gangs in different settings on a case-by-case basis. Indeed, my research in Haiti revealed the limitations of applying templates from one context to another: programmes that successfully disarmed, demobilised and reintegrated rural militias in sub-Saharan Africa could not be replicated when trying to deal with urban gangs in Port-au-Prince.

What's next? Where are the research gaps?

A comparative analysis of how humanitarian actors negotiate safe access in different urban settings could help move forward the debate on how to engage with urban armed groups. This applies not only to fragile and conflict-affected cities such as Mogadishu, but also to cities in countries that are not currently at war but where gang violence is notorious, such as Rio de Janeiro in Brazil or San Pedro Sula in Honduras.

Here the experience of humanitarian agencies such as Medecins Sans Frontieres and International Committee of the Red Cross could provide important insights and lessons learned.

Moritz Schuberth (moritz.schuberth@gmail.com) completed his PhD in Peace Studies at the University of Bradford. This article is based on an interview conducted by Kate Lewis.

It draws on 'To engage or not to engage Haiti's urban armed groups? Safe access in disaster-stricken and conflict-affected cities' published in the October 2017 issue of Environment & Urbanization, which is available under open access until 22 November.