Knowledge equals power! Learning together

IIED has long recognised the transformative power of shared learning and exchange of experience. Across its research groups, learning groups provide platforms for stakeholders across the world to tap into each other’s expertise, share skills and impart best practices.

These learning groups have helped build awareness of key issues, improve tactics for governance work, influence policy in countries and communities, and shape more socially and environmentally just decisions.

Alberto Monterroso: Small producer agency in the globalised market

Alberto is director of the non-governmental organisation Organización para la Promoción Comercial y la Investigación (OPCION) in Guatemala, where he works on rural development — researching and implementing approaches to strengthen the organisational, productive and commercial capacities of small-scale farmers in Central America. He is also president of Comercializadora Aj Ticonel, a company that produces, packages and exports vegetables to Central American, US and European markets.

"Two years ago, I was invited to join a global learning network to combine action research and learning on some of the critical challenges facing small-scale producers in globalised markets.

"I was keen to get involved — both to contribute the results of my fifteen years experience working with smallholders in Central America and to harness the expertise of others working in this field elsewhere.

"The network links people from different regions. We live in different realities but it has become clear that we face the same challenges. The problems hindering the development of Guatemalan indigenous producers — limited access to markets, lack of technology and precarious conditions — are similarly thwarting small-scale producers in Kenya or Uganda.

"By sharing knowledge and experience, all members of the learning group gain fresh perspectives for change. During a meeting last year in Fort Portal, Uganda, we met local farmers and not only discussed the challenges they face, but more importantly shared how we have overcome them.

"The network also provides a critical platform for broader impact at home. Through it, I am working to build a new consensus in Central America about how governments can best support smallholders. Part of that includes campaigning for a Central American fund, supported by individual governments, to provide financial support for small-scale farmers. This is a clear example where the network is already beginning to contribute a wealth of practical knowledge, and where the strength of working together on the same topic really comes into its own."

Related resources: Small producer agency in the globalised market | A Global Learning Network at work | Making markets work for small-scale farmers? A series of ‘provocation’ seminars

Sanjay Upadhyay is an environmental lawyer in India, with a wealth of experience in forest governance. In 1999, after completing four years with the World Wide Fund for Nature India, he established the country’s first environmental law firm, the Enviro-Legal Defence Firm, in New Delhi, where he remains a managing partner. Sanjay is also an advocate of the Supreme Court of India, fighting court cases and negotiating with the government on a range of forest issues.

"I have a long history of collaborating with IIED — before joining the Forest Governance Learning Group (FGLG) in 2006 I worked on a range of projects with the institute. But the FGLG is different.

"There are ten countries involved in the group, across Africa and Asia. I don’t often get the chance to work on a comparative basis with African countries in particular and the group has given me a unique learning opportunity to experience, and learn from, other country contexts.

"Our challenges are not country-specific: the struggles on forest tenure or pro-poor strategies for reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD) are global concerns — and it is always good to know how different countries are tackling them. Sometimes, what has worked in one country helps you understand your country context better. But this type of global learning also allows you to learn from other people’s mistakes.

"FGLG is not just another network ... we are making a real impact on millions of people’s livelihoods and wellbeing in India."

- Sanjay Upadhyay

"Being part of FGLG has made me a better advocate — not many Supreme Court lawyers can draw on first-hand experience in Malawi or Bali to build a case in court or negotiate for action with our government.

"And it has helped me exert an influence where it really matters. FGLG is not just another network — it is a group of serious people who truly matter when it comes to making decisions about forests. From drafting the country’s first Forest Rights Act to writing a letter that has become the guiding note for enabling tribal communities to use bamboo, we are making a real impact on millions of people’s livelihoods and wellbeing in India.

"I hope that we as a group can find the resources and people to allow FGLG to continue beyond existing funding commitments. It has great value in terms of ideas, strategies and experience, which can actually resolve issues of forest governance on the ground.

Related resources: Forest Governance Learning Group | Just forest governance: how small learning groups can have big impact | Justice in the forests - a series of short films | Shifting power in forests

Backroom work on biodiversity

In October 2010 biodiversity policymakers, researchers and advocates gathered in Nagoya, Japan for the 10th Conference of Parties to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). The CBD conferences are always beehives of intense activity but this year tensions were running particularly high.

The enormous pressure to strike a deal was driven in part by the world’s failure to meet the CBD target to significantly reduce the rate of biodiversity loss by 2010 and growing concerns that we are nearing ′tipping points′ in which whole ecosystems could collapse.

But negotiations were also fraught by the contentious issue of access to genetic resources and benefit sharing. Developing countries insisted that a protocol on these issues be finalised before assenting to the two other main agenda items: a deal on financing and a strategic plan for the convention. It wasn’t until the very last minute that agreement on all three issues was reached.

The enormous pressure to strike a deal was driven in part by the world’s failure to meet the CBD target to significantly reduce the rate of biodiversity loss by 2010 and growing concerns that we are nearing ′tipping points′ in which whole ecosystems could collapse. But negotiations were also fraught by the contentious issue of access to genetic resources and benefit sharing. Developing countries insisted that a protocol on these issues be finalised before assenting to the two other main agenda items: a deal on financing and a strategic plan for the convention. It wasn’t until the very last minute that agreement on all three issues was reached.

The enormous pressure to strike a deal was driven in part by the world’s failure to meet the CBD target to significantly reduce the rate of biodiversity loss by 2010 and growing concerns that we are nearing ′tipping points′ in which whole ecosystems could collapse. But negotiations were also fraught by the contentious issue of access to genetic resources and benefit sharing. Developing countries insisted that a protocol on these issues be finalised before assenting to the two other main agenda items: a deal on financing and a strategic plan for the convention. It wasn’t until the very last minute that agreement on all three issues was reached.

"Scope and compliance are key to achieving a successful protocol... You do not want a toothless protocol where issues are excluded."

- Peter Munyi, International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology, Kenya

Throughout the highs and lows, and in the run-up to Nagoya, IIED, FIELD and partners were there — following negotiating sessions, organising side events, and promoting findings from our work. We focused on three key areas of activity: influencing benefit-sharing negotiations; supporting negotiators from small island states; and working with journalists.

Gains for Indigenous communities

When Southern countries agreed to conserve biodiversity and use it sustainably at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio, it was on the understanding that they would benefit from the use of their genetic resources by Northern countries. But the past two decades have seen very little benefit sharing with developing countries.

The Nagoya Protocol contains important gains for indigenous and local communities. It legally binds the 193 parties to the CBD to follow rules to prevent biopiracy and provide benefits, including financial ones, to countries and communities when using their genetic resources.

Much of this achievement is owed to the tireless efforts of the International Indigenous Forum on Biodiversity over the past six years. IIED supported these efforts by providing evidence of the importance of customary laws and rights based on research with more than 60 communities in the developing world.

In the year leading up to Nagoya, we worked hard to influence the negotiations, both directly — through formal submissions and statements and UK DEFRA consultations — and indirectly, through policy briefings, side events and media work.

Standing with small island states

To successfully take part in high-stake conferences like the one in Nagoya, countries need capable teams of negotiators that can understand the breadth of issues discussed, navigate intricate sessions and events, and stand firm on key issues.

Heaving with complex legal issues, and against a back-drop of certain failure to meet the 2012 target to establish comprehensive, effectively managed and ecologically representative protected areas, the marine and coastal biodiversity negotiations turned out to be controversial and lengthy.

Negotiating teams from small island states — with limited resources, expertise and technical support — faced a considerable disadvantage in participating effectively. The Foundation for International Environmental Law and Development — until March 2011, an IIED subsidiary — supported delegates from these states and other developing countries on legal matters during drafting sessions, regional coordination meetings and negotiations.

Newsroom networks

In Nagoya, parties to the CBD agreed that by 2020 all people should be aware of the values of biodiversity and the steps they can take to conserve and use it sustainably. To meet this target, global media coverage of biodiversity will need to improve in quality and quantity — showing how biodiversity underpins economies, livelihoods and wellbeing but is under serious threat the world over.

Nicole Leotaud, Caribbean Natural Resources Institute, TrinidadAt the COP, I heard a lot of passionate communities... identify the need to share more with others so they can scale up the impact of their work. They are calling for support and assistance to build their capacity so they can benefit and we can have biodiversity conservation as well.

Journalists need training and more access to sources and information if they are to tell this under-reported story and what it means for humanity. To support this, IIED, the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Internews created the Biodiversity Media Alliance, launched in Nagoya.

The alliance has created an online social network — http://biodiversitymedia.ning.com — where more than a thousand journalists and biodiversity experts can interact. Over the longer term, it aims to develop training for journalists to report biodiversity in ways that are relevant to their audiences.

Related resources: Biocultural Heritage website | Convention on Biological Diversity COP10 | Biodiversity Media Alliance

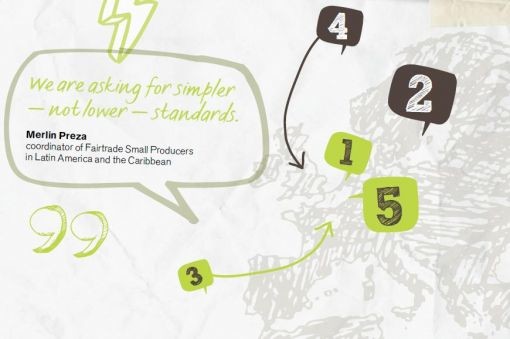

Provoking big debate about small agriculture

Small-scale agriculture is well and truly back in the development spotlight — as the future to global food security, a route to rural poverty reduction, a steward of natural resources and a key to climate change mitigation and adaptation.

But if the need to support small-scale agriculture is agreed, the way forward remains highly contested. There is certainly a role for markets and the private sector. Indeed, many development policymakers and practitioners speak about ‘making markets work for the poor’ as the key to securing economic development, growth and prosperity.

But how best can we do that? Should we emphasise markets or rights? Is large agribusiness a partner in development, or a driver of exclusion? Do we support smallholders or wage labourers? How do we ensure the most vulnerable and marginalised benefit?

An IIED/Hivos knowledge programme, Small Producer Agency in the Globalised Market, has sought to stimulate debate on these issues that are ‘stuck’, through a travelling series of provocative seminars across Europe — in The Hague, Stockholm, Paris, Manchester and Brussels. The ‘provocations’ brought new and challenging insights on the role of markets and business in the future of smallholder agriculture.

Holding the ‘provocations’ in Europe was no accident. By contesting conventional wisdom and presenting fresh perspectives in European powerhouses, the knowledge programme got up close and personal to those within the development community — donors, investors, researchers and businesses — who hold real power and influence in shaping pro-poor markets.

Some of the challenges facing small-scale farmers are highlighted in a video playlist – click on the playlist below to see all the videos.

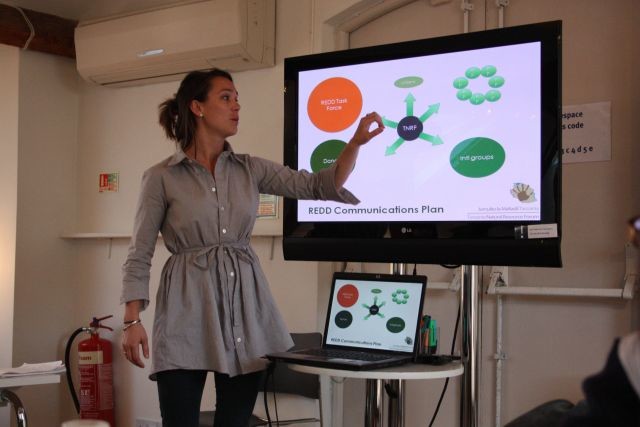

Cross-cultural learning in communication

For researchers to shape effective policy and practice for sustainable development we must communicate with decision makers on their terms. They need robust evidence that gives them confidence, context-relevant information that supports their own situation, and an understanding of the practical realities facing their constituents and other people they are trying to support.

Communicating research in a way that delivers on all these counts is difficult and varies across contexts and cultures. One way to rise to the challenge is to share lessons from what works across different countries and sectors. In February 2011, IIED’s communications team brought together nine researchers, communicators, advocates and project managers from partner organisations for a week-long opportunity to do just this.

IIED’s Communication Learning Week covered a broad range of skills and tools, including crafting a communication strategy, writing for policymakers, working with the media, exploiting new technologies such as social media and participatory video, marketing publications and monitoring results.

Participant perspectives

I came into the week with relatively high expectations...but the week certainly lived up to them. It was personally a great learning experience for me and for TNRF too — I will be able to go back and bring a lot to the organisation...

It was great to have just nine participants. I was really able to troubleshoot and workshop my own issues, and make a lot of progress — not just talk in theory about things. And it was wonderful to hear from people with similar struggles and challenges to those we face in Tanzania — bureaucracy and politics but also simple things like trouble with internet connections. It was even more positive to hear how people overcome these challenges and I feel like I learnt a lot from my peers.

In short, I’ve gained a lot of wonderful tools, made great contacts and I now feel I have some real concrete ideas to bring back to my organisation

- Jessie Davie, Tanzania Natural Resource Forum (TNRF), Tanzania

What I liked most about the learning week was that the sessions were very interactive and participatory — even when I didn’t expect them to be — and that got everybody moving and made the whole programme quite exciting. The sessions on policy briefs and working with the media were particularly powerful and I drew a lot of energy from that. It’s an important area for us in Uganda to work on and see how we can improve.

I strongly feel that you could take this work forward with a mentorship programme, especially in the area of working with media and policymakers — because of our need to grow the language appropriate for engaging in and communicating about the different issues we deal with.

- Christopher Busiinge, Kabarole Research and Resource Centre, Uganda

The Communication Learning Week was a great opportunity for me to improve my communication skills and put in place a communication strategy for my organisation. I’ve been doing lots of good work at home but how to communicate what I do to the public and local community has been a constraint. This week has helped me learn how to market my organisation and communicate well with donors and with local community people themselves.

The facilitators were friendly, especially to those of us coming from different social backgrounds — they created a friendly environment where we freely interacted with one another with no fear. The week provided a lot of opportunities to make new connections, including with journalists and others that we have had little opportunity to meet before.

My one recommendation would be to extend the time for practically doing some of this work with facilitators on hand to help. Writing a policy brief is not something you can do in one day

- Salome Gongloe Gofan, Rural Integrated Centre for Community Empowerment, Liberia

Related resources: Cross-cultural insights into communication | Making communication count: a Strategic Communications Framework | Development online: making the most of social media

African youth in participatory politics

Across the world we can see experiments in ‘participatory governance’. People and organisations are grasping opportunities provided by decentralisation and other reform processes and demanding more of a say in the public policy and budget processes that affect them.

From participatory budgeting in Brazil to monitoring elections with mobile phones in Kenya, a growing range of citizen-led mobilisation, activism and demands are holding governments to account and giving a voice to the people not usually heard in formal policy and governance processes.

But exciting as these new approaches are, we need to look harder at them. Are they working for all or are some voices still left out? In particular, are they working for the young? In Africa, the debate on who is a ‘youth’ continues. Some countries use the UN definition of 15 to 24 years. We define youth as the time of transition from dependence (childhood) to independence (adulthood) — an age range that varies widely across contexts.

In March 2011, IIED, Plan UK and the Institute of Development Studies brought together a group of adults and young people involved in youth and governance initiatives across Africa at a ‘writeshop’ in Nairobi, Kenya. The idea behind the week-long meeting was to share learning and experiences, build writing skills, form new relationships, and develop a set of articles for a forthcoming special issue of IIED’s journal Participatory Learning and Action (PLA).

"This week’s writeshop has really helped me to think about applying more detailed analysis to my work on youth and governance… The process has bridged the gap between learning and application."

- Leila Billing, ActionAid International, Zimbabwe

Powerless to participate

During the writeshop, contributors acted out how young Africans commonly perceive governance processes and their scope for engaging in them. Their scenes included:

-

A tight circle of adults surrounding a girl, propelling her from one to the other, while she looked increasingly dizzy and confused. Her mouth was sealed with masking tape.

-

A girl and boy lounging against a wall, their faces and attitudes oozing boredom: nails being filed, gum chewed. In the background, an adult types madly at a desk while another strides around looking busy and efficient — neither ever looking at the youths.

-

An adult puppet-mistress pulling the strings of a girl puppet, walking her up a conference hall to the stage. There the puppet curtsies, handing over a rolled-up speech to an adult dignitary, who pats her on the head before she is puppeted away.

The scenes presented in Nairobi speak eloquently of tokenism, presence without influence, condescension, well-meaning but power-blind political correctness, frustrated potential and dissipated energy, and generational and gendered power hierarchies. It is these fractured patterns of engagement that the contributors to this issue of PLA are working to change.

"What has really excited me is that issues about young people in governance are beginning to be placed on the table, and on the agenda for NGOs and governments; as well as learning how this is a common thread that runs across Africa."

- Lipotso Musi, World Vision, Lesotho

Beyond youth stereotypes

Throughout the writeshop we heard practitioners from across Africa describe how youth — particularly boys — are seen, and see themselves, as a ‘lost generation’: disaffected and bored with life, and infinitely corruptible and corrupted.

But we also heard tales of how young Africans — who make up more than half the continent’s population — are challenging the norms and structures that exclude them by engaging with the state and demanding accountability.

Youth in Sierra Leone are using participatory video to get local government to address weaknesses in service provision. And in Sanaag, a disputed territory between Puntland and Somaliland, youth are leading a unique community survey called the Camel Caravan to engage with pastoralists.

The Nairobi writeshop uncovered the vibrancy, energy, persistence, passion and enthusiasm that youth bring to decision-making processes. It showed us that young people can drive change in creative and unexpected ways.

The forthcoming issue of PLA will highlight how young Africans are doing this — addressing the documentation gap that surrounds youth and governance in Africa and enabling other participatory practitioners, both young and old, to learn from their experience.

Text adapted from McGee, R. with J. Greenhalf (forthcoming 2011) ‘Seeing like a young citizen: Youth and participatory governance in Africa’ Participatory Learning and Action 64.

Photostory: PLA writeshop in Kenya

In March 2010, IIED, Plan UK and the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) brought together a group of adults and young people involved in youth and governance initiatives across Africa at a ‘writeshop’ in Nairobi, Kenya for IIED’s journal Participatory Learning and Action (PLA).

Related resources: Participatory Learning and Action

Big business from small growers

Some of the world’s largest food companies are committing to development by opening their supply networks to small-scale producers. Through its Sustainable Living Plan, Unilever has pledged to trade with an extra 500,000 small-scale farmers by 2020. Walmart plans to triple sales to more than US$1 billion from a million small and medium farms in emerging economies. Both are looking beyond the fair trade niche or token corporate social responsibility projects, to align with mainstream business.

While such linkage to modern markets may not yet provide livelihood opportunities for most smallholders in developing economies, it warrants serious study to understand what underpins inclusive business.

As part of a project led by the Sustainable Food Lab, IIED has spent three years working in a chain that links up to 4,000 small-scale Kenyan farmers to export markets in Europe and North America via a highly innovative local intermediary. The product in question is flowers, grown as part of family farming systems. A half acre of flowers generates more income than four acres of the other main cash crop tea, with significantly less labour.

Linking worlds

The Kenyan case study is marked by a shift from ‘pushing’ flowers at Dutch flower auctions to a ‘pull’ market, driven by demand from UK and US supermarkets. The supermarket business model is built on fixed procedures, uniformity and compliance with standards. It puts considerable strain even on the best smallholder-based model, and challenges the usual calls to cut out the middleman and build independent producer organisations.

"Know-how and understanding in agricultural and business practices are the biggest hurdles to development. Understanding the end user helps them [smallholders] create a better matched product."

- Wilfred Kamami, Executive director, Wilmar Agro Ltd, Kenya

Setting a target for sourcing supplies from smallholders is just the start. In this case, the business models of the intermediary, the importer, the retailer and the certifier all have to change to link the worlds of smallholders and modern business. This should be backed up by regular health checks: IIED is now working with Kent Business School to develop practical tools for businesses to assess their trading relationships.

Related resources: New business models for sustainable trade | Under what conditions are value chains effective for pro-poor development - summary paper | Investing in smallholders and workers is good for business

Greening the economy from the grassroots up

At next year’s Earth Summit in Rio (Rio+20), the words on everybody’s lips will be ‘green economy’. Across the globe, people are already working to build a clear vision of those words and decide what policy and action is needed — at global, national and local levels — to turn the vision into reality.

Over the past year, the Green Economy Coalition — a diverse group of organisations from different arenas and geographies — has contributed to that effort. Through a series of national dialogues, the coalition, which is housed at IIED, is learning about the reality of green economy debates in different cultural and ecological contexts. It is gathering insights on policy needs. And it is stimulating new civil society ownership of the term ‘green economy’.

"If we want to make it in the 21st century, which will be largely defined by resource constraints in an evermore inequitable world, then we need everyone’s brains and actions to work together."

- Mathias Wackernagel, Global Footprint Network, United States

Green economies need deep roots

In India, the story you usually hear is one of rapid progress: impressive growth rates of 8.5 per cent; a doubling of energy demand over the past decade; and consistently healthy domestic investments at 35 per cent of GDP. But participants in the Indian national dialogue also told another tale — one of enduring poverty, environmental degradation and growing inequalities. Look beneath the statistics and you’ll find that agriculture — which employs more than half the country’s workforce — is in crisis. Many of the poorest people in India still lack even basic access to energy. And the infrastructure behind the rapid growth still relies on unsustainable products and materials.

Participants called for urgent transformation to a green economy. They want a system that “creates decent employment opportunities — green jobs — and produces green products and services with equitable distribution and sustainable consumption leading to regeneration of the environment”.

The Indian dialogue is one of four held over the past twelve months, alongside ones in Brazil, Caribbean and Mali. Another six are planned for the coming year. All will influence the Green Economy Coalition’s policy positions in Rio+20 and set the tone for broader debate.

"The green economy needs to rethink growth, rethink development and be more inclusive — not just of nature but also of people, particularly those who have been left out of the economic system."

- Juan Marco Alvarez, International Union for Conservation of Nature, Switzerland

What is a green economy?

From each national dialogue run by the Green Economy Coalition, a different understanding of green economy has emerged.

-

In India: priorities are agriculture, renewables, green jobs, construction and infrastructure.

-

In Brazil: green economy is seen as wellbeing and social equity, tackling environmental risk and managing ecological resources.

-

In Mali: green economy methods show how growth in incomes and livelihoods can be achieved in ways that sustain the natural resource base and build resilience to climate change.

-

In the Caribbean: it means long-term prosperity and effective ecological resource management.