How can we engage communities to help reduce illegal wildlife trade?

Engaging local communities is recognised as a key approach to tackling the illegal wildlife trade. But a key problem remains: deciding what to do, and how to do it.

Turtle hatchlings, targeted by the illegal wildlife trade, are pictured on a beach (Photo: Wildlife Rescue and Conservation Association)

Wildlife crime is at the top of the international conservation agenda. IIED and its partners, including the IUCN Sustainable Use and Livelihoods Specialist Group (SULi), and the Centre of Excellence for Environmental Decisions (CEED) at the University of Queensland, have developed a 'theory of change' for understanding how community-level interventions can help in tackling illegal wildlife trade, which we present here.

Do the 'pathways' we present reflect your experiences from illegal wildlife trade-related projects and programmes? Do the assumptions that we suggest hold true?

IIED is looking for feedback from people who have experience in this area on our approach to this issue.

What is the problem?

Poaching and the associated illegal wildlife trade are devastating populations of iconic species such as rhinos, elephants and tigers, as well as a host of lesser known ones.

The current approaches to tackling this can be broadly classified into three types:

- Increase law enforcement

- Reduce demand, and

- Support sustainable livelihoods and local economic development.

To date, most attention has been paid to the first two approaches with relatively limited attention given to the third. The reason is that, while people agree we need to engage local communities in order to tackle illegal trade in wildlife effectively, they don't know what to do, and how to do it.

When it comes to engaging communities effectively, it is clear that there is no one-size-fits-all solution. So thinking through 'pathways to change' that can lead to a reduction in illegal wildlife trade through different forms of community engagement, and unpacking the assumptions underpinning each step in those pathways, can help design effective approaches for involving communities in tackling illegal wildlife trade.

Proposed method

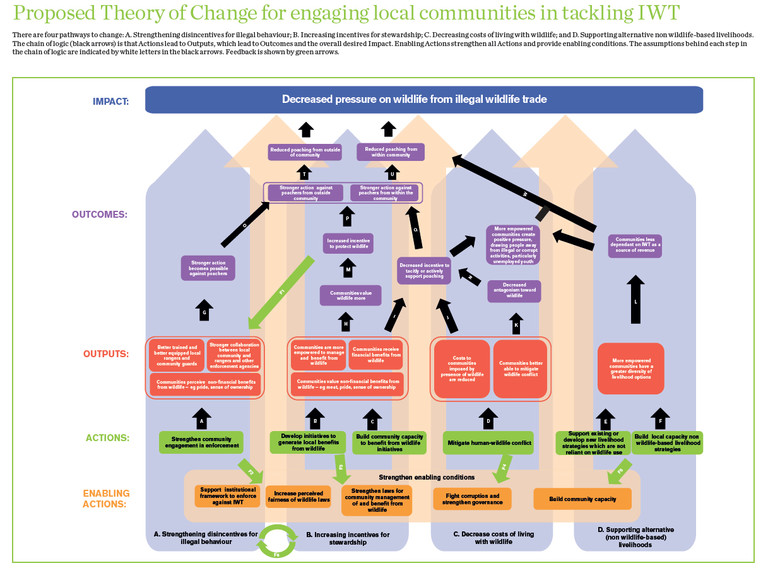

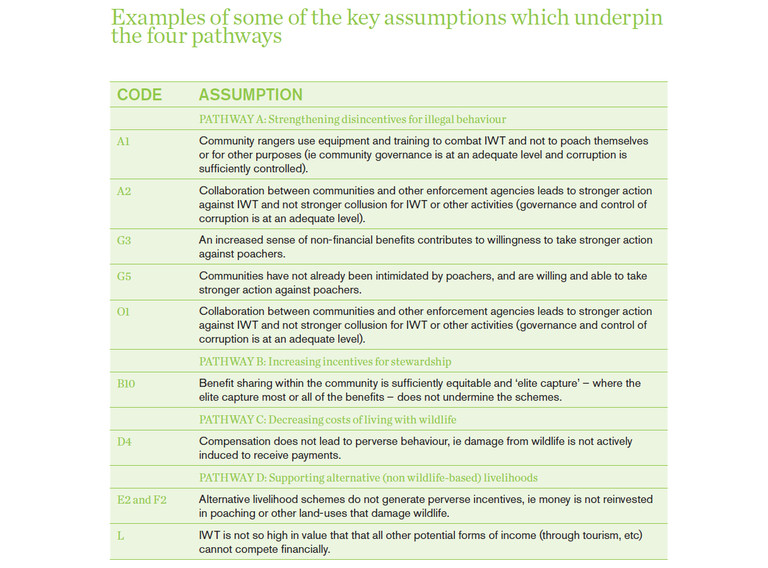

In 'Engaging local communities in tackling illegal wildlife trade. Can a 'theory of change' help?' the authors present a draft theory of change to explore four different approaches to engaging communities in tackling IWT. This theory of change can be viewed below alongside a table of nine key assumptions underpinning the theory of change – click on each image to expand them. The theory of change can also be found on IIED's Flickr website, where users are further able to magnify it.

Each of the four pathways involves consecutive community-level actions, outputs and outcomes that lead to a common desired impact: decreased pressure on wildlife from illegal trading in wildlife. The four pathways are:

- A: Strengthening disincentives for illegal behaviour. This pathway involves making it more difficult and costly to trade poached wildlife

- B: Increasing incentives for stewardship. This pathway involves strengthening both the financial and non-financial rewards for protecting and sustainably managing wildlife

- C: Decreasing the costs of living with wildlife. This pathway involves reducing the burdens of living with wildlife, and

- D: Supporting alternative (non-wildlife) livelihoods: This pathway involves creating livelihood and economic opportunities not directly related to wildlife, such as bee-keeping or craft development.

Join the discussion

We want to hear from people with direct experience of engaging communities and tackling illegal wildlife trade 'on the ground' to join our discussion on how useful this approach is and how well our draft theory of change represents these complex issues.

Please read the report and share your thoughts and ideas in the comments section below, through this survey or directly to my email via d.biggs@uq.edu.au by the end of September 2015.

We would like to know your thoughts on the following questions:

- Is a theory of change a useful approach to help policymakers and practitioners think about how and where to invest resources in community engagement to tackle illegal wildlife trade?

- Do the four pathways that we articulate make sense to you? Are there other pathways for engaging communities in tackling the illegal wildlife trade?

- Do our suggested outputs and outcomes make sense? Are there better alternatives or additions?

- Do the assumptions hold true in the illegal wildlife trade settings with which you are familiar? Are there additional assumptions that we are missing? We are particularly interested in your feedback on the nine assumptions listed in the table above; these are a selection of the assumptions from annex 1 of the report.

- Are there other key enabling or disabling conditions that we have overlooked?.

Thanks very much for taking part in the discussion.

Duan Biggs (d.biggs@uq.edu.au) is a research fellow in the Centre of Excellence for Environmental Decisions and the Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Science at the University of Queensland. The discussion paper 'Engaging local communities in tackling illegal wildlife trade. Can a 'theory of change' help?' was funded by UK Aid from the UK government. However, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the UK government.